Precision, patience, and philosophy. The core of Japanese watchmaking. What began as a class became a celebration of human craft in a digital world. Seiko didn’t just teach us how a watch works; they reminded us why it matters.

It’s not every day that the spirit of Japanese watchmaking travels beyond its homeland. Yet for a few extraordinary days, Seiko brought that very essence to Australia, flying two master watchmakers all the way from Japan to host the brand’s first-ever international watchmaking experience. This was an event that I had very much been looking forward to for a long time. It’s not every day that Australia experiences a true watchmaking event where you actually get to pull apart the movement, so it is safe to say that a lot of us watch enthusiasts were waiting in anticipation.

The fact that Seiko brought this incredible opportunity to not only Australia, but Brisbane first shows how much they value the Australian audience. Being the first nation and city in the world to experience this was spectacular, and even that is an understatement, given Seiko’s rich history and worldwide popularity. The atmosphere before the watchmaking event was charged with anticipation, as collectors and enthusiasts gathered not just to observe the master watchmakers but to get hands-on with the intricate art of mechanical watchmaking, guided by the same steady hands that bring Seiko’s legendary timepieces to life.

The night prior to this exclusive event in Brisbane, Seiko collaborated with WatchAdvice for the global launch of the new Seiko Prospex Limited Edition ‘Kame’ Divers Watch. This launch was certainly a one-of-a-kind, and if you’ve been to prior Seiko launches, you know they like to go the extra distance to put on a spectacular night. And what a night it was! Held at Brisbane’s Bouganvillea House at Howard Smith Wharves, the house was packed with Seiko collections, and fun activities such as the racing simulator (with the new Seiko Supercars edition being awarded to the driver with the fastest lap time!).

The launch celebrated not just the craftsmanship of Seiko, but also its commitment to marine conservation, with the ‘Kame’ paying tribute to turtle preservation efforts across Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. With this being the very first Seiko event in Brisbane on this scale, it was an incredible night. What made it even more special was the fact that it really put Brisbane on the map for watch events, as this was also an official “global launch.”

The following morning, the fun kicked on for us watch enthusiasts, with select guests who attended the ‘Kame’ launch the night before being invited to something even more exclusive, and a world first for Seiko: a private watchmaking workshop, the first of its kind not only for Brisbane, but for Seiko outside of Japan. To say that this was a privilege for us Brisbanites would be an understatement. It was an event not to be missed, as the chance to do a watchmaking class of this calibre very rarely comes around.

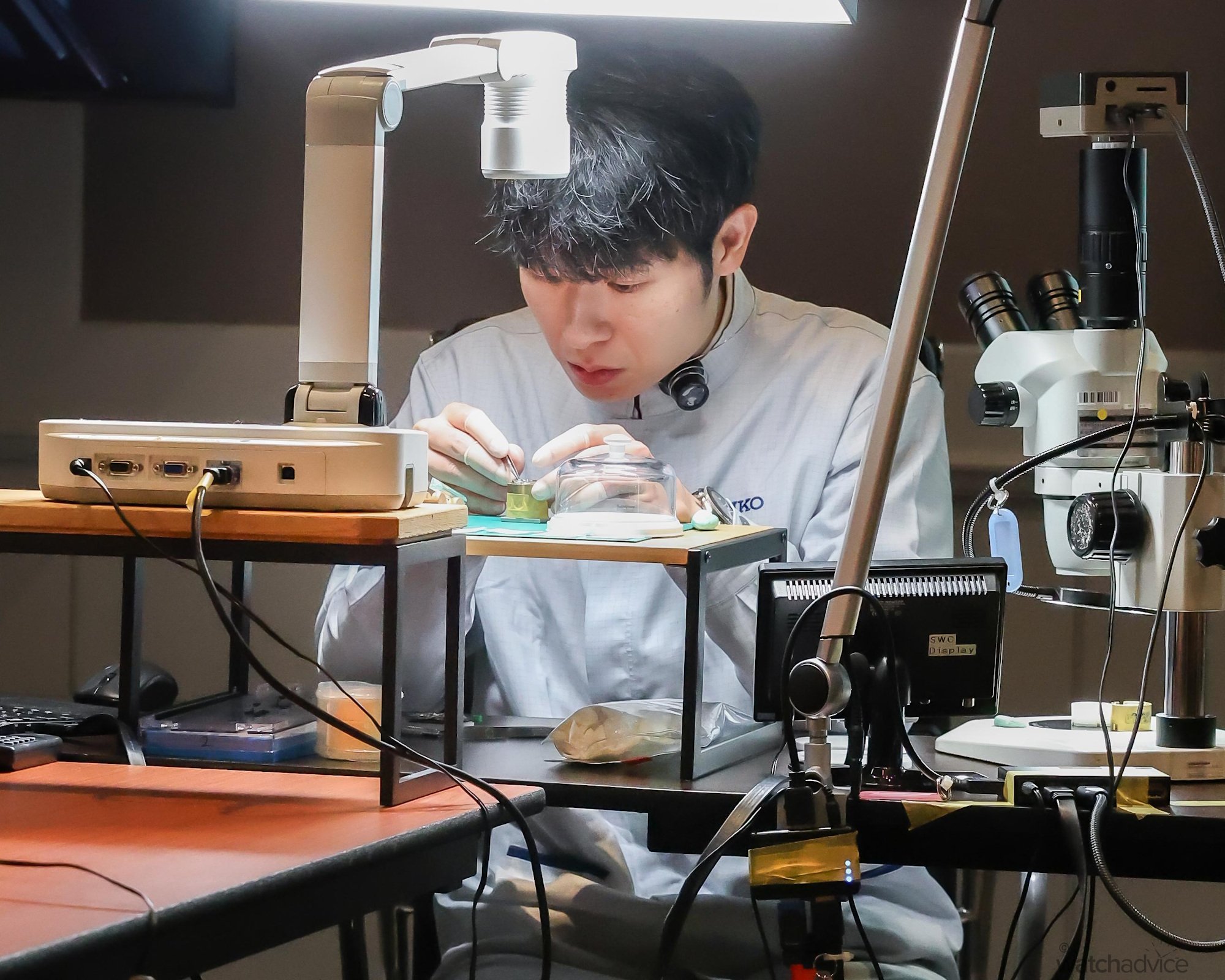

Located in the heart of Brisbane City, these special watchmaking classes took place at the Marriott hotel, with a conference room transformed into a classroom of precision, focus, and wonder. There was a total of 10 seats for the “students”, with each seat having its own miniature workstation: watchmaking tools neatly laid out, magnifiers ready, and tiny mechanical movements waiting to be explored.

As we all made our way into the Marriott hotel, the energy outside the watchmaking room was buzzing with excitement. As we waited outside, there were various conversations between the guests about the night before, the new ‘Kame’ release, and the surreal prospect of learning directly from Japanese watchmakers. Everyone was ready in anticipation, not just to see the Japanese watchmakers in action, but to take apart a piece of horological history with their own hands!

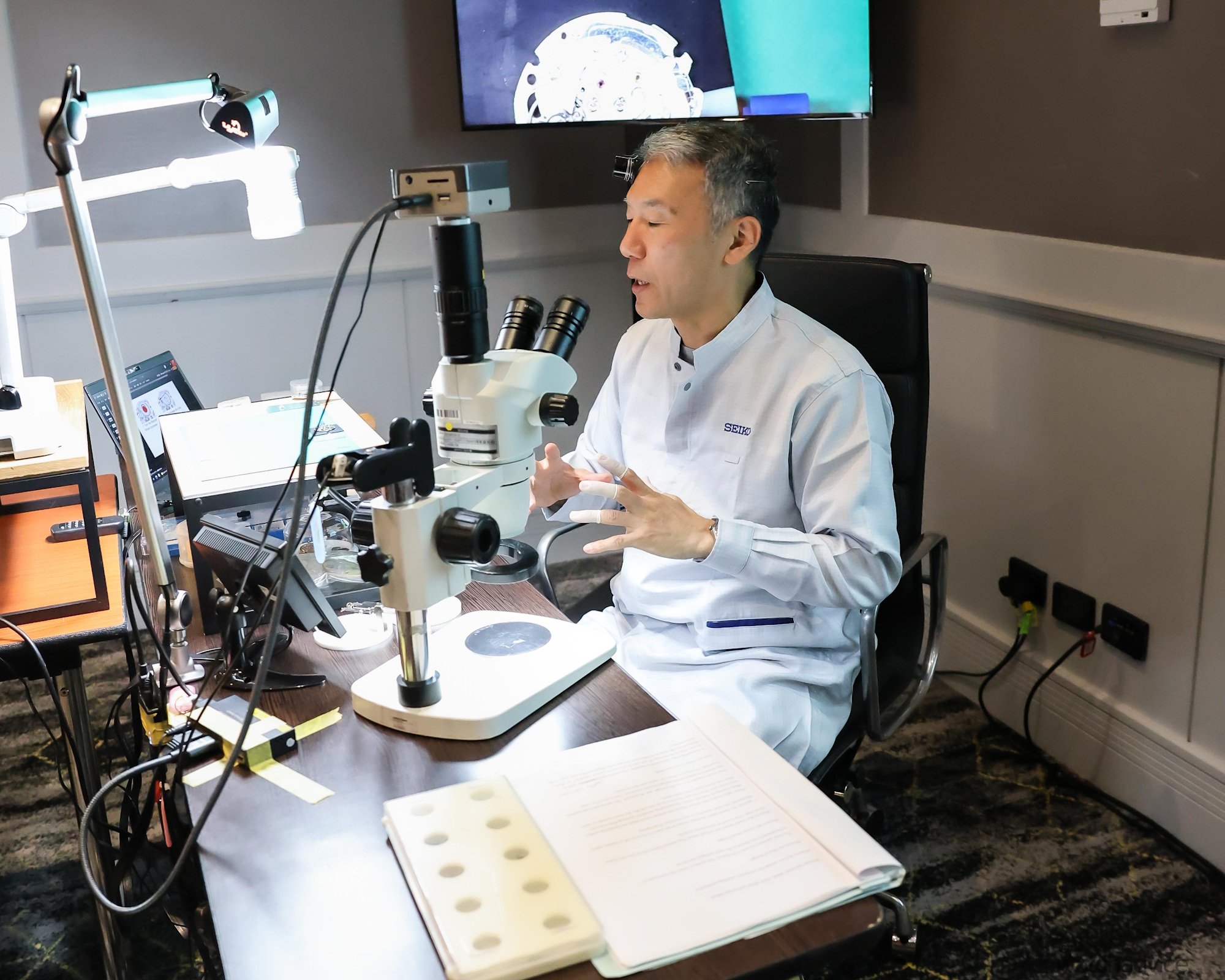

As we made our way into the watchmaking classroom, each of the guests took a seat at one of the ten workstations. We were greeted by the Managing Director of Seiko Australia, Ms. Kinuyo Sakata, a Japanese watchmaker, Hiroharu Tanaka, one of Seiko’s technical trainers, Makoto Sakai, and, of course, Dan and Brett, the representatives for Seiko Australia.

Introduction & Demonstration – Calibre 8L35B

Before the class officially began, the two Japanese watchmakers took centre stage and offered us a rare glimpse into their world. Both watchmakers were incredibly humble when talking about their journeys into watchmaking, stories that began with childhood fascination and evolved into decades of discipline, precision, and passion. Between the two, they carried over twenty years of watchmaking experience at Seiko, having spent most of their careers fine-tuning the movements and bringing some of the most memorable and iconic Seiko timepieces to life.

Listening to them speak was both inspiring and grounding: you could feel the respect they had for this craft, from their meticulous work ethic, the steady hands, and the insane patience they have developed, to the pride they have in representing one of the most revered watchmakers in the world. I, myself at this point, wondered what life would be like to live in Japan and work as a watchmaker, to wake up each day surrounded by the rhythmic tick of timepieces, dedicating your life to mastering the art of watchmaking.

They spoke about what it’s like working at Seiko, a brand that is built not only on heritage, but on the relentless pursuit of improvement. Inside the Shizukuishi Watch Studio in northern Japan, where many of Seiko’s high-grade mechanical movements are assembled by hand, the art of watchmaking isn’t just a skill; it’s a way of life. Each watchmaker undergoes years of rigorous training before they’re trusted with the full assembly of the movement, and this was reflected by their discipline in having calm, deliberate movements and their quiet confidence.

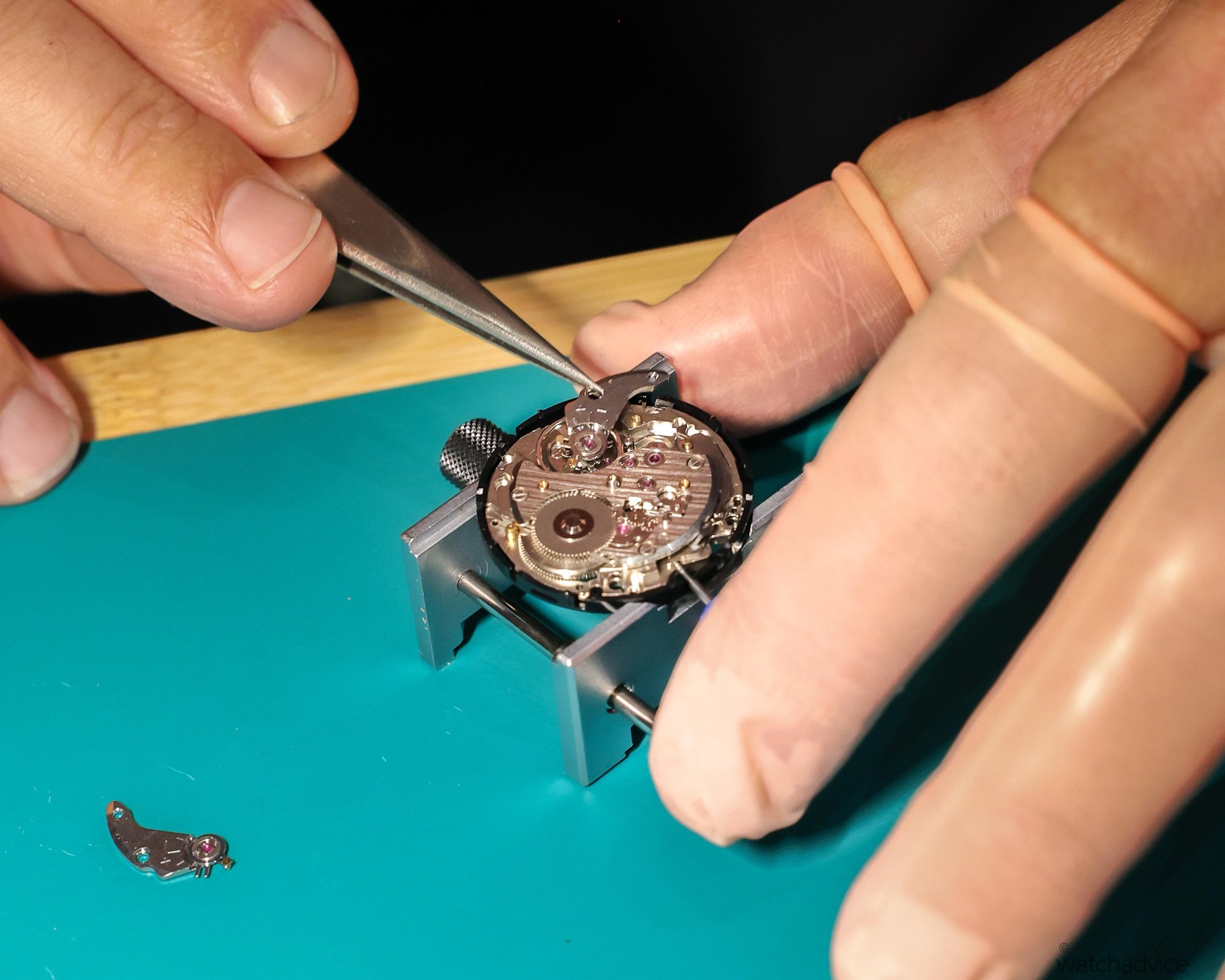

After the introductions were over, the two watchmakers gave a demonstration of dismantling the Seiko Calibre 8L35B movement. The Calibre 8L35B movement is a true workhorse, designed and assembled entirely in Japan. This is the same movement that powers Seiko’s Prospex Dive watches (professional grade), which includes the models that have been inspired by the Master Marine line. The movement is also derived from the Grand Seiko 9S55 architecture, which means that it shares the same DNA with some of the finest mechanical movements in the entire watch industry.

The watchmakers then began their demonstration of dismantling the Calibre 8L35B movement, a seamless, twenty-minute exercise that felt like choreography. They had a display setup behind their watchmaking station, which would show us on the screen a close-up view of them disassembling the movement. Under the soft glow of their bench lights, they methodically disassembled the 8L35B, revealing the intricate layers that make up the movement’s beating heart, before reassembling it again with astonishing ease. Watching them at work made it all look deceptively simple and gave us all confidence, but as we were about to find out, the real challenge was yet to come.

It’s as they say, “The calm before the storm”.

Preparing for Precision: Tool Familiarisation

Before we started the process of dismantling our own Seiko 4R movement, we first got accustomed to the tools at hand. The first exercise we did, however, was to determine which eye was our dominant one, something not many of us knew we could even test, and honestly, it was pretty cool to try. It began with the Japanese watchmakers showing us a dot on the PowerPoint screen. Then, they asked us to point at the dot using our dominant hand. Next, we closed one eye to see if our finger still covered the dot, then repeated the same with the other eye, keeping one closed each time.

What you’ll notice is that with one eye, your finger perfectly covers the dot, while with the other, it appears slightly off — that’s how you find your dominant eye! (Try it at home if you didn’t know already!) The reason for this exercise was to determine which eye the loupe, the head-mounted magnifier, would go on. This is the eye you’ll be using to carry out all your watchmaking duties!

After this, the watchmakers then took us through all the various tools and apparatus that we will be using for the watchmaking session, which I have given a brief overview of below:

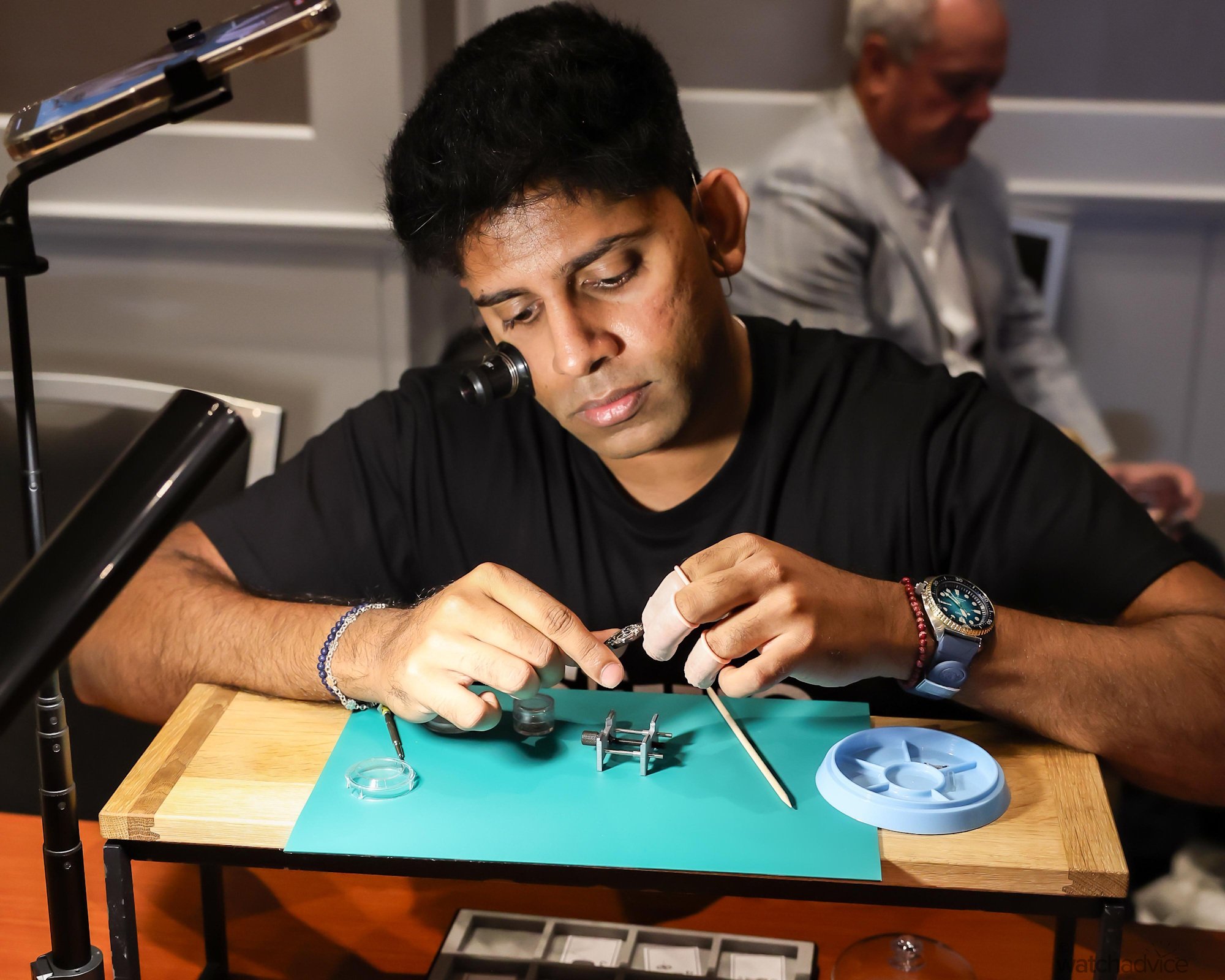

Watchmaker’s Tweezers (Antimagnetic)

Precision tweezers are a watchmaker’s best friend. They are used to pick up screws, gears, and other incredibly tiny components. I can attest to the fact that they require incredibly steady hands for use! Made from non-magnetic steel, they ensure each part is safely handled without breaking any components or, when taking the calibre apart, doesn’t disrupt the delicate balance of the movement.

Movement Holder (Adjustable Movement Clamp)

The movement holder is another important tool. Although I would say this is somewhat of an apparatus, as it’s only got one purpose, and once set, you don’t need to adjust or touch again. The movement holder does exactly what the name says: it is a small clamp that securely holds the watch movement in place while you work. The adjustable arms on the holder can be adjusted to fit calibres of varying sizes, ensuring the movement doesn’t slip or shift during assembly. The important thing is that it’s in securely, before you clamp it down, something I didn’t do initially, and made the first few steps of the disassembly harder!

Watchmaker’s Screwdrivers

The watchmaker’s screwdrivers are an essential tool for loosening and tightening the screws of the movement. Luckily for us, the Calibre 4R movement used all the same screw sizes for the disassembly process that we conducted; otherwise, normally the watchmakers would have various screwdrivers that are colour-coded by size. This is certainly where some of that patience and dedication come into play.

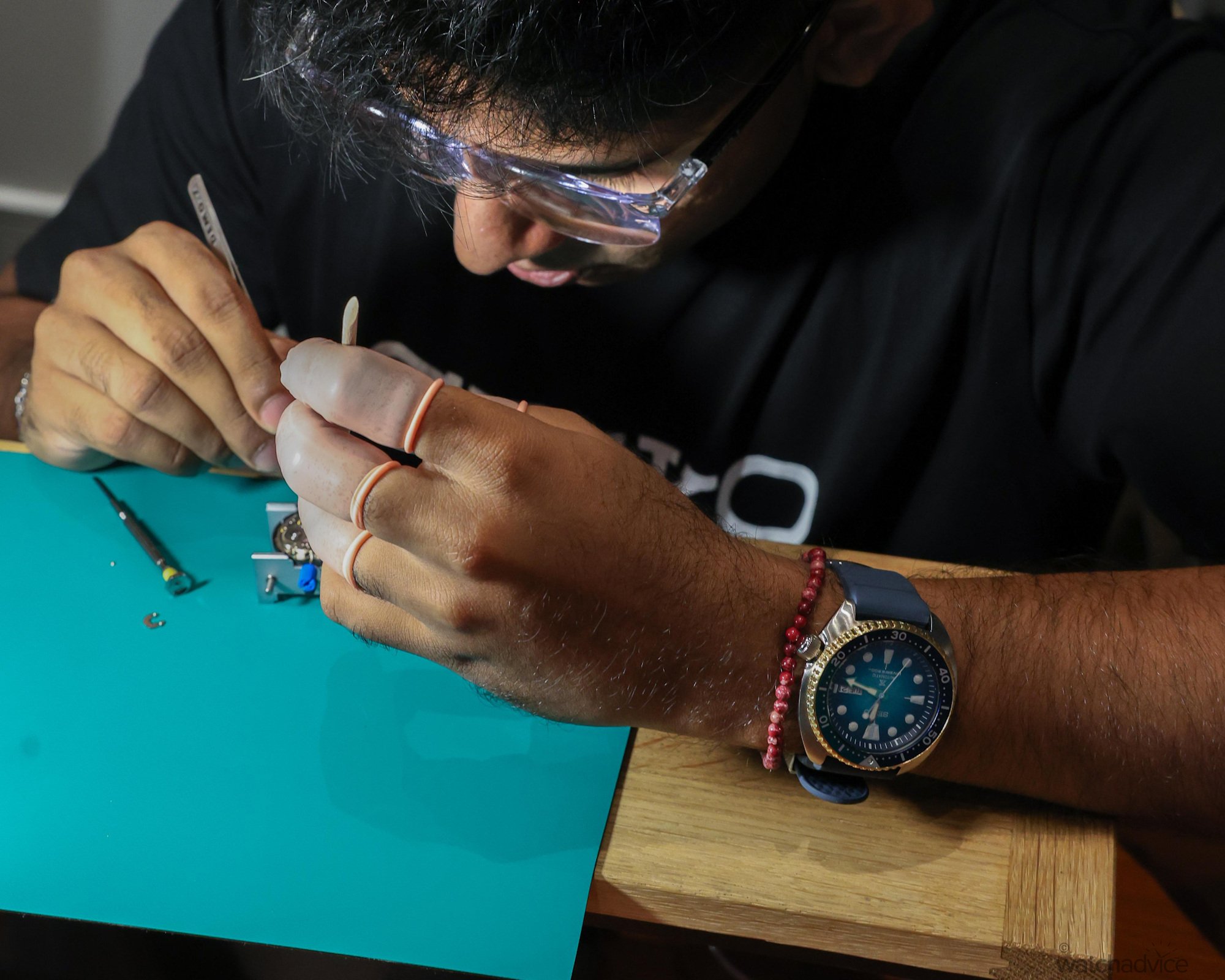

Loupe (Head-Mounted Magnifier)

The head-mounted loupe allowed participants to see every intricate detail of the movement up close. With how tiny some of the parts of the movement are (some screws can be thinner than a single hair-strand!), you definitely need a magnifier to see it in a much larger scale, especially when using the screwdriver or watchmaker’s tweezers. With magnification just strong enough to reveal each jewel and gear, it gave us a new appreciation for how small and delicate everything really is. Once you look through it, you can’t unsee how intricate watchmaking truly is.

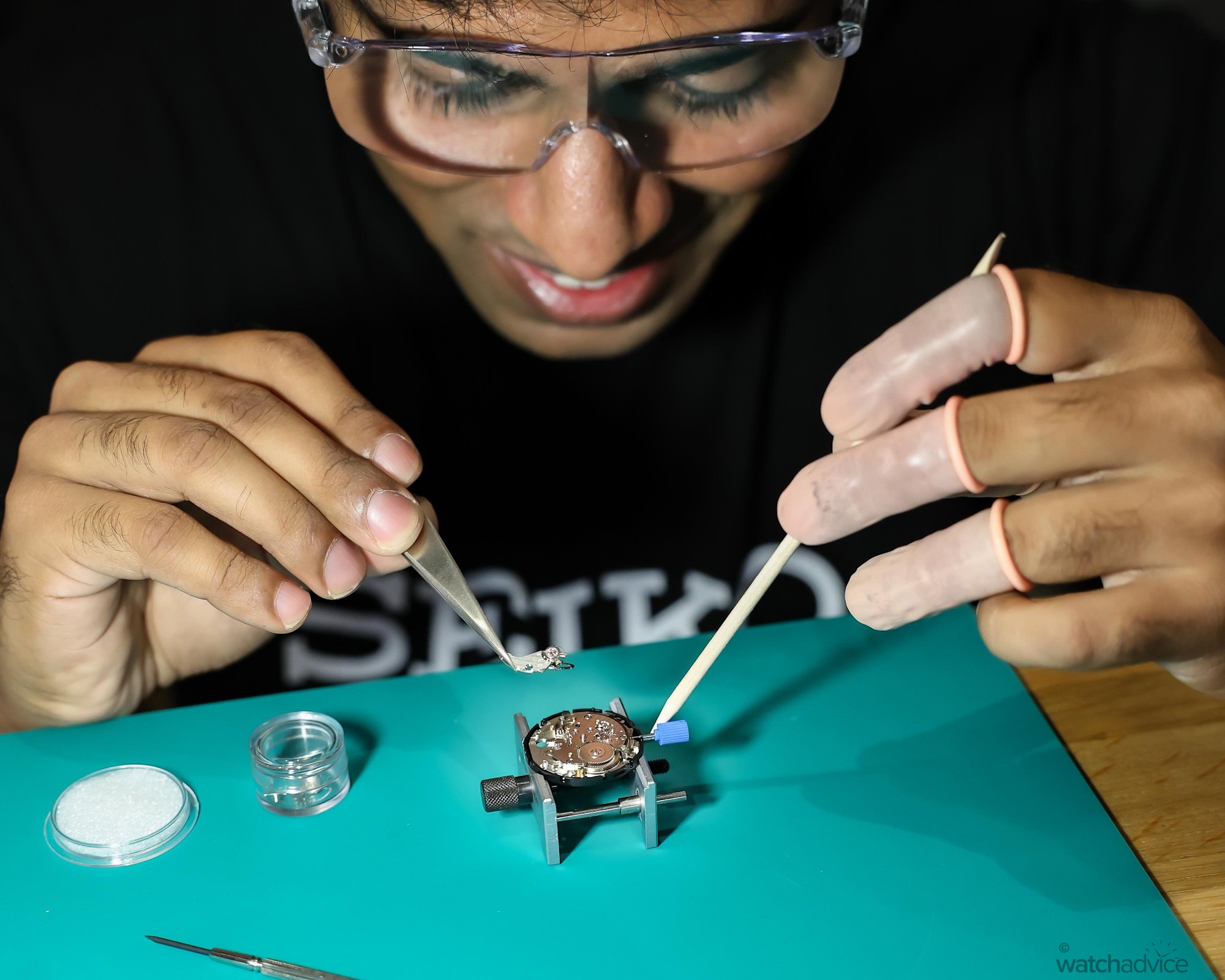

Finger Cots (Rubber Finger Covers)

Instead of full gloves, each participant wore latex finger cots, protecting both the components and the wearer. These keep natural skin oils, dust, and moisture away from the movement, all while maintaining a sense of touch. It’s a subtle reminder that even fingerprints can affect precision.

Pegwood Stick

This is a simple yet surprisingly versatile tool; the pegwood stick is used to clean, nudge, and adjust components without leaving scratches. When a certain gear doesn’t sit in place quite correctly, or when the balance cock just doesn’t feel like fitting into its place, the pegwood stick can be used to slowly and smoothly nudge them into position without leaving any marks. Made from boxwood, it can be sharpened to a fine point for detailed work. It might look basic, but it’s indispensable for fine mechanical tasks.

Parts Tray (Movement Tray)

For our watchmaking session, underneath every table worktop, we had a rectangular box that was used as a parts tray. This is where every removed part finds its temporary home. For us novices, the parts tray was split into different compartments, with a detailed image of the part that would be placed into it. This ensures nothing gets lost or mixed up during the process. Considering how small some of these screws are, the tray quickly became our safety net.

Dust Cover (Glass Dome)

When a movement isn’t being worked on, it’s placed under a glass dome to keep dust at bay. Even a single speck of dust can interfere with the performance of a mechanical watch. This simple cover symbolises the obsessive care that defines Seiko’s craftsmanship.

Watchmaker’s Mat (Anti-Static Work Mat)

The green mat on every desk wasn’t just for aesthetics. It prevents static buildup and provides a stable, non-slip surface for all the tools. It’s soft enough to cushion components if dropped, yet firm enough to work on comfortably. A small but vital part of a professional setup.

Dismantling The Seiko 4R Movement

I won’t take you through the entire dismantling process of the movement, because honestly, it would take the fun out of it if you ever get to experience a watchmaking class yourself. Some things are best left as surprises! What I can tell you, however, is that the process is both humbling and incredibly satisfying. It teaches you patience and shows just how steady your hands need to be to dissect all the intricacies of a movement. Watching a complete movement slowly come apart piece by piece gave me a newfound respect for the precision that goes into every Seiko timepiece.

Armed with the watchmaker’s tools —tweezers, screwdrivers, and a pegwood stick- we began carefully removing the components. We were carefully guided by the two Japanese watchmakers through PowerPoint slides for each component that needed to be dismantled. For this particular watchmaking class, the winding rotor had already been removed for us, meaning we could dive straight into removing the top plates and screws that held the Seiko Calibre 4R movement together.

Each component was delicately lifted and placed into its own section of the parts tray. From the balance bridges, gears, and levers, all the tiny mechanisms that, when combined, make time itself tick. Every turn of the screwdriver required focus, patience, and an impossibly gentle touch. Even the smallest slip could send a microscopic screw flying into oblivion, and trust me, this was no joke. Several of us in the class lost screws due to how delicately they need to be handled.

One of the most fascinating stages of the dismantling process came when we reached the mainspring barrel. The very component that is responsible for storing the watch’s energy. Inside it lies a tightly coiled spring that is held in tension, acting as the heart that powers the entire movement. When it is gently released, the barrel spins freely, releasing that stored energy in a captivating display. Watching this unwind felt like time itself being released. A moment of mechanical life that perfectly reflects the beauty of horology.

As we continued working through the movement, we uncovered the gear train, an intricate series of wheels that transmit energy from the mainspring to the escapement. Under the loupe, you could see how each gear was connected to the next with absolute precision. No wasted movement and space, no friction that was beyond necessary. Seeing it laid bare reminded me just how much artistry hides behind something as simple as a second hand moving across a dial.

Finally, we reached the core of the movement, the part that gives the watch life and its level of precision: the balance wheel and escapement. The true heartbeat of a timepiece, this was also the most delicate part to dismantle, and I can attest the most nerve-wracking. The balance wheel, if you weren’t aware, oscillates thousands of times per hour, regulating every tick of the watch with astonishing accuracy. Holding this component between a pair of tweezers felt surreal. It’s the component that keeps time ticking continuously, and keeps it beating consistently.

This was one of the last components before we had dismantled the Calibre 4R movement for this class. All the components of the movement we had taken apart lay bare in the parts tray, giving us all a deeper understanding of what makes watchmaking so deeply human.

Reassembly: The True Test of Patience

While the disassembly process went surprisingly smoothly, with only a few lost screws throughout the class, we all made it to the end with fair ease. However, as we were soon about to find out, this was the easy part. Taking the movement apart was one thing, but putting it back together with precision and alignment was entirely something else. This is where the true test for a watchmaker begins.

One of the last steps in the disassembly was the removal of the balance cock and the escapement mechanism. This means that the most crucial part of the movement was also the first steps in the reassembly process. No pressure. The escapement consists of a pallet fork and escape wheel (if you want to learn more about it, click here!), and getting both to fit back into their position was no small feat. This was then followed by the careful positioning of the balance wheel and balance cock assembly. The trick was to lower the balance wheel so that its staff aligned perfectly with the jewel below it, allowing it to swing freely once connected. Easier said than done.

For me personally, this stage required multiple attempts and plenty of deep breaths. The moment the balance wheel didn’t line up perfectly, you knew immediately. It was simply about fitting the balance wheel and balance cock back into their position. You actually have to pivot the balance wheel first, then re-align the balance cock into position. If it didn’t align with the escapement, the wheel wouldn’t tick, or the escapement would jam ever so slightly, throwing everything out of rhythm. It was a delicate dance between precision and patience, and if something wasn’t seated correctly, the entire movement had to be dismantled again to fix the alignment. There was no shortcut to this process, just patience and perseverance!

Once the hardest part of the movement reassembly was complete, and the escapement and balance wheel, and balance cock were finally secured, the rest of the assembly process flowed a bit more smoothly. The bridges, gears, and screws all began to fall into place, layer by layer, until the movement slowly came back to life! This was like putting together the world’s smallest and intricate puzzle, and as we drew closer to the end, we started to really appreciate just how interconnected every piece was.

When it all finally clicked, quite literally, and the balance wheel began to oscillate back and forth again, the feeling was indescribable. That soft, rhythmic “tick-tick-tick” was like music after 2 hours of silence. Around the room, small cheers and sighs of relief could definitely be felt as each participant brought their watch back to life. For a brief moment in time, we all felt like part of the Seiko watchmaking family.

Reflection: Why Mechanical Watchmaking Still Matters

As the workshop drew to a close, it became quite clear that this experience was far more about than just taking apart a movement. In a world where smartwatches dominate with wrist notifications, fitness tracking, and endless software updates, it’s easy to forget the quiet beauty of traditional watchmaking. A smartwatch might tell you the time, but a mechanical watch will remind you of it. From every beat of the balance wheel, every gear that is set in motion, is a testament to the human ingenuity and craftsmanship that technology will simply never create.

Speaking with the fellow watch enthusiasts around me at the watchmaking session, there was a shared sense of awe. Many mentioned wanting to go home and try dismantling a movement themselves, inspired by what they just took part in. It was as if the workshop had reignited that childlike curiosity, the desire to understand how something works, rather than simply accepting that it does. You could see it in everyone’s eyes: that deep appreciation for the artistry behind every tick of a mechanical watch.

Of course, at the heart of all these emotions was the quiet beauty of Japanese watchmaking. From the way the humble Japanese watchmakers explained each component and guided us all through patience, the methodical way they moved, there was a quiet philosophy in their approach to watchmaking. The perfect blend of patience, discipline, and respect for the craft. It reflects everything that Seiko stood for: the pursuit of perfection through simplicity, dedication, and purpose.

I’ve been around watchmakers, have attended a few watchmaking classes (although never took apart a whole movement), but I think it’s safe for me to say that this Seiko watchmaking experience left a lasting impression on me. Not only did it showcase the brand’s dedication to craftsmanship, but it also reminded us why we fall in love with mechanical watches in the first place.

Unlike the smartwatch that is replaced every few years, a well-crafted mechanical watch endures time. It can be passed down from generation to generation, repaired, and then brought back to life by the very hands of the watchmakers we met during this watchmaking class. For everyone in that room, it wasn’t just a workshop; it was a celebration of time itself, and a reminder that true watchmaking, especially the Japanese kind, will always have a heartbeat of its own.