We travelled to Le Locle to sit down with Zenith’s Head Of Product, Romain Marietta and Heritage Director, Laurance Boddenman, to talk about the history of Zenith, the widely applauded G.F.J and the start of a new era for the brand.

Earlier this year, we had the opportunity to visit the Zenith Manufacture in Switzerland. It was a great couple of days spent with the team from Zenith, and we were able to see firsthand how the first integrated Swiss watch Manufacture designs and creates its watches. Given that the Zenith Manufacture in Le Locle is still exactly where Georges Favre-Jacot set up shop all the way back in 1865, it also has a heap of history within its archives to show, which, for watch lovers, is an amazing educational experience.

What’s more, we were able to meet many of the people who work for Zenith, from the designers of the movements to the watchmakers assembling them, to the product team who work to bring the pieces to life. However, two of the more important people helping drive Zenith forward are Romain Marietta, Zenith’s Head of Product, and Laurence Boddenman, Zenith’s Heritage Director. Romain has a wealth of knowledge when it comes to the products, designing them and bringing them to life in conjunction with Sébastien Gobert, Zenith’s Head of Design and the wider product and design team. Laurence, while still young, possesses a wealth of knowledge regarding Zenith’s past and how the Le Locle brand draws inspiration from its past to move into the future. We sat down with both Romain and Laurence to discuss the new G.F.J. release, why this piece is so important for the brand, and how the Calibre 135 was, and is, a step forward in a new direction.

Being Zenith’s Heritage Director, Laurence kicks off our talk and explains why the Calibre 135 in the new G.F.J. was revived to help celebrate the 160th Anniversary, as well as being placed inside the G.F.J.

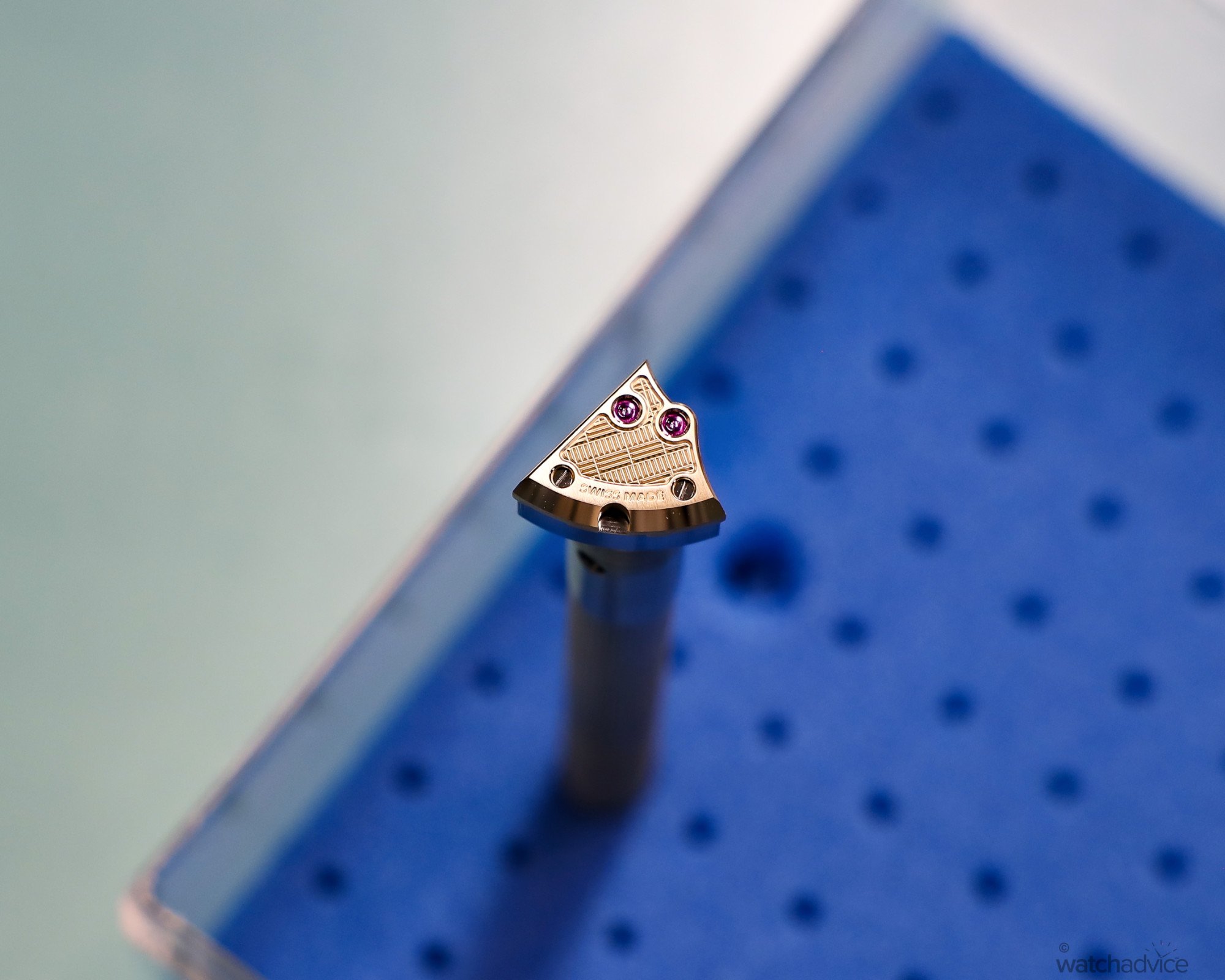

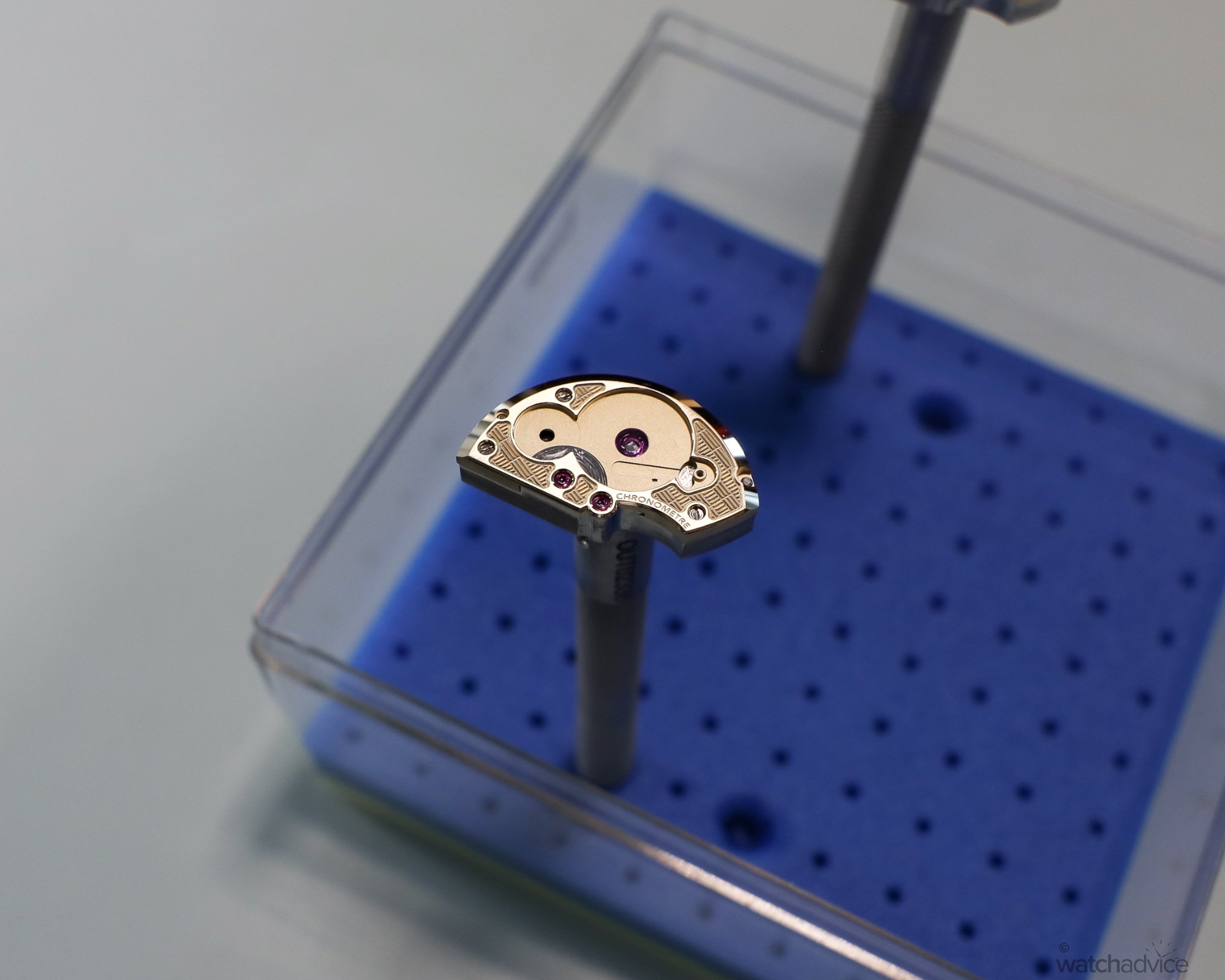

“The Calibre 135, as we name it, is an icon of watchmaking. Because of its different architecture with this extra-large balance wheel, you cannot help but recognise it. And the fact that it was developed to compete and to win the competitions of chronometry gives it a super huge aura that Zenith has been building on, and its history within the 1950s. Today, we wanted to pay tribute to this again because we are celebrating the vision of Georges Favre-Jacot, GFJ, who had this idea and the dream of the perfect watch. So that’s why, basically, we wanted to redirect and invest in this, resurrecting the 135 calibre to make it the icon of tomorrow.”

And you may be asking, what is the Calibre 135, and why was it named this? Well, if you have read our article on the G.F.J. release and our visit to the Zenith Manufacture, you may know this, but rather than me stealing Laurence’s thunder in this article, I’ll let her explain.

“Well, 135. That’s 13 for 13 lignes, which is 30mm (diameter). It’s the biggest diameter you could have to enter the chronometry competitions within the category of wrist watches. So that’s why there are 13 lignes, or 30mm. Then there is a 5mm height of the calibre. So you make 13 (lignes), and 5 (mm in height). That’s 135!”

We kind of joke that this was a simplistic way of naming a calibre, but it is effective and memorable, plus it means something. Kind of like decades ago when the model of a car, like a BMW 118i was the series number (1) and then the size of the engine, 1.8L. Easy and effective. But, redesigning the new calibre 135 in the G.F.J. was anything but an easy or simple task. You may think that with the old movements and blueprints (hand-drawn on sheets of paper, by the way) to reference, it would be less complex; however, with modern technology and materials, plus the demands of the modern-day watch buyer, an old movement in a new watch isn’t really going to cut it. So Zenith had to redesign the Calibre 135 for 2025 standards. Laurance explains…

“The Calibre 135 isn’t just a like-for-like recreation of the calibre from the late ’40s and early ’50s. We really had to go back to the blueprints and work out how this movement would look today, if we had made it today at today’s standards. Back then, the materials used would not stand up, and things like the power reserve would not either. We, of course, wanted to enhance this extra-large balance wheel, but by adding today’s expectations. So, we added additional power reserve, with 1/3 more power (now 72 hours) and better efficiency in the transmission. Also, all the decorations make it a high-end piece, which the original never had; this had to be factored in as well. So basically, it’s taking all this innovation for which the original watchmaker had to fight for in the 1940s, and bringing it to what we expect a perfect watch to be today.”

To put it in context, talking to some of the product team during our time at the Manufacture, the Calibre 135 in its modern iteration was many years in development, and as a result, all up, including R&D, cost somewhere in the realm of several million Swiss Francs. So even when there is a historical movement to reference, the time and money it takes to create isn’t small. Romain jumps in here to clarify.

“It’s a long but natural process of development, and then brick after brick, you are building the wall of the final product, so to speak. What we did at first was work on the movement. And then brick after brick, we worked on the design, on the case, and on the dial. But at first, the central part of the whole piece is the movement. I mean, just the idea of bringing back the movement was just the craziest idea that we had at first!”

Both Romain and Laurence comment on this aspect – “It’s a huge investment to bring a movement back to life and to further develop it. You have to convince LVMH, the committee here (at Zenith), and the CEO. I (Romain) already discussed this topic ten years ago with Jean-Frédéric Dufour (Zenith’s CEO at the time), but it was not the right time, or the right moment. It’s at least two to three years of development. Would it still be meaningful in three years? Would it be worth the cost? Well, now time will tell, of course.”

And this is probably one of the most interesting facets of the Calibre 135 in the Zentih G.F.J. The time and resources it took to take a 70-year-old movement and bring it back to life with 2025 materials and tolerances. Romain elaborates:

“I mean, it’s sort of a big challenge. The power is the biggest challenge. You managed to take what was 42 hours, and now we have 72 hours of purely efficient power. But in reality, we have 80 to 85 hours of operating power. We have more; we have basically doubled it. Officially, we say that we have had an increase of one-third to 72 hours. But because we have also been able to put everything onto a computer, to do a lot of simulations on the materials, that has helped us.” And on the topic of materials, Laurence explains:

“That’s what we saw from our colleagues from the technical bureau. They challenged everything, including the materials, and nowadays you have materials, like for the balance spring, which react differently from the ones that were in the 1940s. We now have a hacking second, which was not the case on the regular production back then, as it wasn’t needed; the watches were worn every day, and there wasn’t a real need to set to an exact reference time. Added to this, we then went a step further and decorated the movement, so this had to be taken into account too… like the smallest detail in architecture, material, even finishes, have their impact on the final (efficiency) rate”

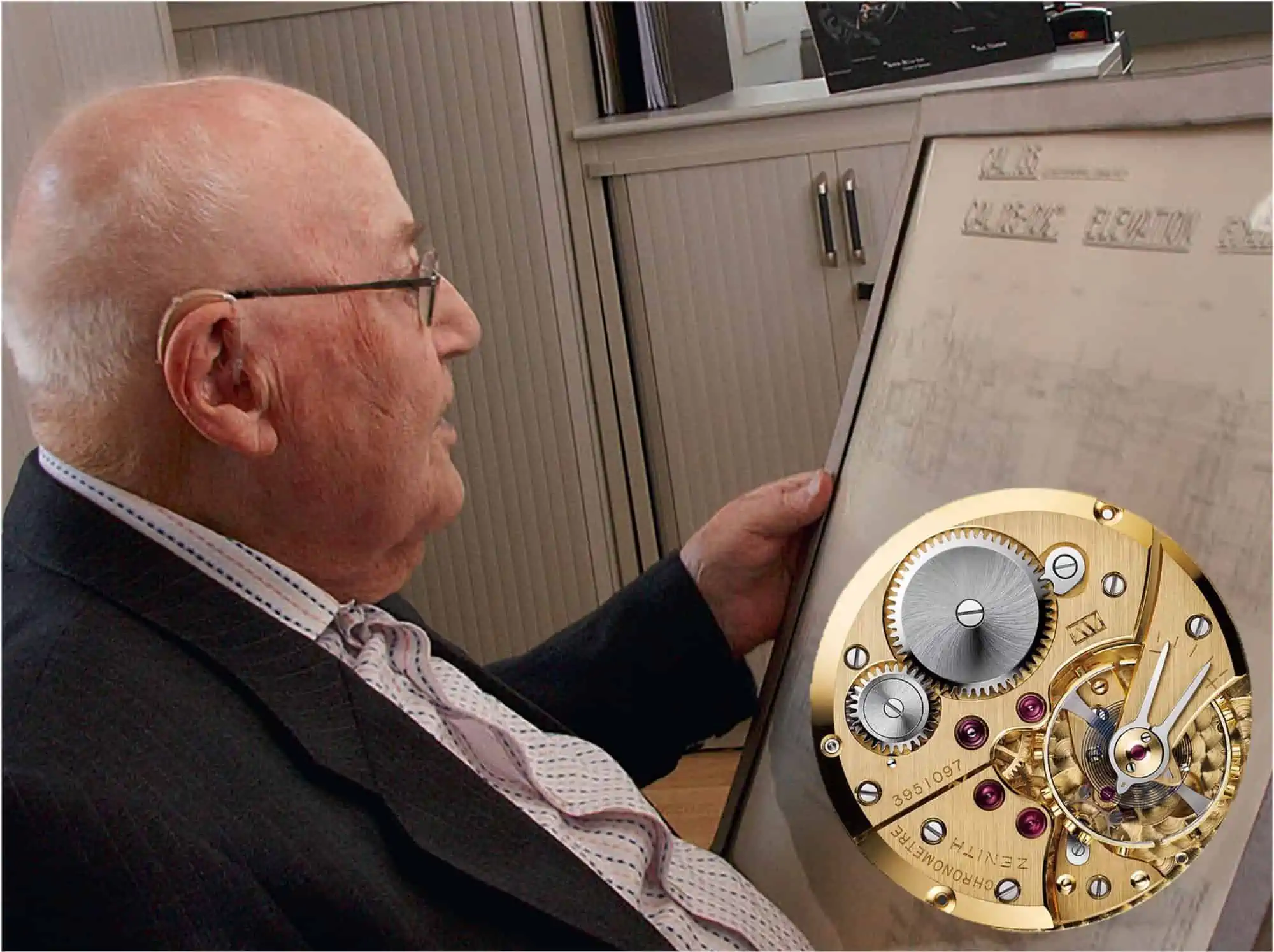

Talking to Laurance, she mentions the original creator of the Calibre 135. The Calibre 135 was originally designed by Ephrem Jobin at the request of Charles Ziegler, Technical Director of ZENITH. In trying to attain the goal set out by Georges Favre Jacot, making the perfect watch, this was a movement that was made to compete in the Chronometry Trials and the Neuchâtel Observatory. In his quest to perfect this watch, Ephrem had quite a lot of internal obstacles in his way (not unlike today), and interestingly, Romain had a chance meeting with the man several years back, who at the time was 100 years old.

“He was kind of a funny guy because he was 100 years old, barely able to walk, and he said himself, I cannot remember what I ate at lunch or at breakfast. But when we showed him the technical drawings, HIS technical drawings of the movement that he hadn’t seen for over 60 years, it was like it lit a fire in him. He was able to explain that (the movement), and it was amazing! He didn’t know what he ate at breakfast, but he could tell you why and how he developed the movement.”

Like with all businesses, even back in the 1940s, the dream of the perfect watch that was passed down from Georges Favre Jacot wasn’t a given. Laurence talks about how Ephrem Jobin had to also fight to create the 135 Calibre, even back then, when the company decided that it would compete at the Chronometry trials.

“And for this development, he (Ephrem) really had to fight because he wanted this extra-large balance wheel, which makes it iconic. He wanted the inertia that it would bring in order to have the stability of beat rate. Basically, when you do so, you have to calculate what you are losing in terms of power reserve and see how you have to rearrange all the bridges and the gear train and so on. So he really fought for his dream.”

And speaking of dreams, or these days in the modern business world, goals, with Benoit de Clerck at the helm of Zenith, the brand has new goals to propel it forward into the future. Even though Zenith is part of the LVMH group, it acts like an independent of sorts. With small production runs compared to the larger players in the industry, Zenith produces about 10,000 watches per year, vs other mainstream brands in the hundreds of thousands of units.

It means Benoit and the team at Zenith are starting to focus on elevating the watchmaking and finishing of their pieces. The G.F.J. is just the start of this process, which we can see from the build, materials used and the decoration and finishing on the movement, case and bracelet (for those who want this as an add-on). Romain explains more on this…

“We wanted to create more value, also being able to demonstrate more of our knowledge, our expertise, and savoir-faire, in the watchmaking field, and basically also enhancing and highlighting our history, paying tribute to the big chapter of chronometry pieces. The G.F.J collection is going that way. It is paving the way for our thoughts and thinking for the future novelties to come. As an example, the next movement that we are going to bring to market is going to be in 2027.”

“The other main idea is really about the G.F.J. becoming a collection, complementary to the others. The Defy is very contemporary, the Chronomaster is very much the soul of who we are, and Pilot is another collection where we are expressing ourselves. So it was logical in a way. Not only that, but we are also working on fewer quantities and more value, so it makes perfect sense…We will elevate our level of finishing and quality. That’s not that we are not quality now, but we really want to keep on going in that direction, because we want to establish ourselves for the future, for the next 160 years – that’s the main goal here.”

And when you look carefully at the G.F.J. and the Calibre 135, you can see what Romain is talking about here. There are levels to the watch itself, from the faceted platinum case with multiple finishes to the dial that has the Lapis Lazuli main dial, Mother of Pearl small seconds and then the brickwork guilloché around the edges. All with the Zenith Blue that represents the sky. All these elements came from different areas of inspiration from other models as well – like the tri colour subdials, which are reflected in the three shades of blue, the Mother of Pearl that was used on a prototype Chronomaster gave inspiration for the use on the G.F.J and the brickwork pattern Guilloché, from the manufacture itself.

This is Zenith signalling that it can enter the world of Haute Horlogerie, and go head to head with some of the more well-known independent brands, who are gaining more traction with watch enthusiasts over the past few years.

Romain reinforces this. “It’s true. We cannot deny it, the fact that we are witnessing what’s happening for the independents, for all these three hands, time only watches that are coming into the market, sometimes with less meaningfulness, history and legacy. It makes sense for us to bring back this (calibre 135). The idea is not to compete against these guys because it is not at the same level, and not everything is made by hand. To clarify this, the majority of this movement is made by hand, but it’s not at the same kind of finishing (as a Kari Voutaleinen, or Rexhep Rexhepi, as an example). But it’s not at the same price point, either. I don’t think people are expecting this from us. Nor are we going to follow the trend either, we want to bring something to the table that is special and a little different, plus this is a certified Chronometre, which many others at this level are not”

Romain makes a good point here. Quite often, we see high horology in a time-only watch that isn’t Chronometre certified, and yes, the finishing is exceptional, which is what you are paying for, along with the watchmaker’s expertise, but the accuracy isn’t ensured. What Zenith is doing here is striking a balance between higher-level finishing, quality materials and a movement that has a good power reserve and is accurate with the certification to back it up. Based on Zenith’s testing, the Calibre 135 is within Master Chronometre standards. Laurence jumps in on this point:

“And we can bring in the certification as a chronometer, which they do not. Some of the biggest names claim to be Chronometre standard, but they’re not. It’s written Chronometre on some of their watches, but they’re not a Chronometre. It’s crazy. So this is what we can bring, aside from the high-end finishing and so on, the quality, and vouching for this stability and accuracy of the movement.”

How the team at Zenith has balanced all the elements of the G.F.J is actually quite good. They have managed to bring to market a watch that not only celebrates the 160th Anniversary of Zenith in a meaningful way, but one that collectors will want to have in their collection. Spending a week at Watches & Wonders this year, you heard time and time again what a good job Zenith did with the G.F.J from both watch media as well as the higher-end collectors at the fair. With this, a price point that isn’t overly ambitious either, given the make-up of the piece itself. Romain explains the thinking here:

“We took our time to bring back another, hopefully, great movement within the industry. We know it, collectors know it. It’s recognised as such, but now it has to be recognised by the public, by the broader audience. That’s the main goal, even if we will remain very small in terms of quantity, and it needs to represent more value than its relative retail price.” Laurance chimes in as well…

“And that’s it, when you are bringing in something super high-end, you don’t want to say you don’t want it to stay in drawers because people are thinking high-end means too exclusive. So that’s why, in terms of timing, it’s a celebration that is met by a celebration of the skills and the know-how we possess.”

She makes a good point here. Striking a balance between exclusivity and unobtainability can be tricky, especially when a watch is designed for a special occasion with considerable effort, time and money involved. The G.F.J. is the story of Zenith and its founder in a watch. The inspiration, brand cues, the DNA and technical expertise are all different parts of Zenith’s history rolled into a 160-piece limited edition made from Platinum and precious stones. From a price point, at A$78,400, this is good value for money when compared to other pieces such as this on the market.

And if you want to stand out from the already small crowd that will own a G.F.J., then there is always the option to add the full platinum bracelet as well, which will double the cost of the watch. Some have said that it may be a little steep, and an additional A$70,000 or so on a bracelet, but the amount of refined and machined platinum in the bracelet is 168 grams, or about A$7,700 worth, plus whatever is lost in the milling and refining process, so around A$10,000 in raw materials. Also, Zenith hasn’t pulled any punches with this as they have continued the brickwork Guilloché down through the inner links, and continued the bevelling on the external links to mirror the bevelling on the case itself. This alone takes 3x longer to do than it would if it were gold, so the human hours that are spent on the bracelet is considerable.

While other brands have done large-scale activations, big press junkets and brought out a range of very high-end pieces, Zenith has done what it does best, which is focus on its history and heritage as Switzerland’s first fully integrated watch manufacture, and thought about how it best can bring this to life and celebrate with the watch community and wider audience. Overall, the G.F.J. and Calibre 135 are a perfect way for Zenith to celebrate its 160th Birthday on two fronts: Firstly, the story that it allows the brand to tell to bring to life its past, and secondly, a move that signals where Zenith is heading over the next phase of its journey. As Romain says, time will tell if the new G.F.J and revived Calibre 135 will be a success for the brand, but based on the initial feedback and buzz, we would say it most probably will be!

“The G.F.J. collection, which, depending on the success of the Calibre 135, will hopefully be our next major collection. We are very confident, but we have to demonstrate that it’s a success, and then, of course, we can build on that, and then we can really have a roadmap for it. We have ambition, so it is just a matter of having the clients ready to follow us.”